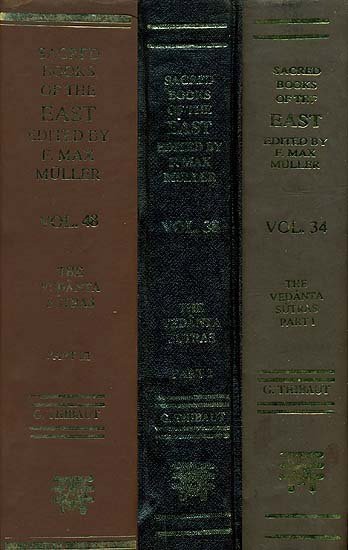

Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.4.6

6. And of three only there is this mention and question.

In the Upanishad under discussion there is mention made of three things only as objects of knowledge—the three standing to one another in the relation of means, end to be realised by those means, and persons realising,—and questions are asked as to those three only. There is no mention of, nor question referring to, the Unevolved.—Naciketas desirous of Release having been allowed by Death to choose three boons, chooses for his first boon that his father should be well disposed towards him—without which he could not hope for spiritual welfare. For his second boon he chooses the knowledge of the Naciketa-fire, which is a means towards final Release. 'Thou knowest, O Death, the fire-sacrifice which leads to heaven; tell it to me, full of faith. Those who live in the heaven-world reach Immortality—this I ask as my second boon.' The term 'heaven-world' here denotes the highest aim of man, i.e. Release, as appears from the declaration that those who live there enjoy freedom from old age and death; from the fact that further on (I, 1, 26) works leading to perishable results are disparaged; and from what Yama says in reply to the second demand 'He who thrice performs this Nāciketa-rite overcomes birth and death.' As his third boon he, in the form of a question referring to final release, actually enquires about three things, viz. 'the nature of the end to be reached, i.e. Release; the nature of him who wishes to reach that end; and the nature of the means to reach it, i.e. of meditation assisted by certain works. Yama, having tested Naciketas' fitness to receive the desired instruction, thereupon begins to teach him. 'The Ancient who is difficult to be seen, who has entered inLo the dark, who is hidden in the cave, who dwells in the abyss; having known him as God, by means of meditation on his Self, the wise one leaves joy and sorrow behind.' Here the clause 'having known the God,' points to the divine Being that is to be meditated upon; the clause 'by means of meditation on his Self points to the attaining agent, i.e. the individual soul as an object of knowledge; and the clause 'having known him the wise ones leave joy and sorrow behind' points to the meditation through which Brahman is to be reached. Naciketas, pleased with the general instruction received, questions again in order to receive clearer information on those three matters, 'What thou seest as different from dharma and different from adharma, as different from that, from that which is done and not done, as different from what is past or future, tell me that'; a question referring to three things, viz. an object to be effected, a means to effect it, and an effecting agent—each of which is to be different from anything else past, present, or future[1]. Yama thereupon at first instructs him as to the Praṇava, 'That word which all the Vedas record, which all penances proclaim, desiring which men become religious students; that word I tell thee briefly—it is Om'—an instruction which implies praise of the Praṇava, and in a general way sets forth that which the Praṇava expresses, e.g. the nature of the object to be reached, the nature of the person reaching it, and the means for reaching it, such means here consisting in the word 'Om,' which denotes the object to be reached[2]. He then continues to glorify the Praṇava (I, a, 16-17), and thereupon gives special information in the first place about the nature of the attaining subject, i.e, the individual soul, 'The knowing Self is not born, it dies not,' etc. Next he teaches Naciketas as to the true nature of the object to be attained, viz. the highest Brahman or Vishṇu, in the section beginning 'The Self smaller than small,' and ending 'Who then knows where he is?' (I, 2, 20-25). Part of this section, viz. 'That Self cannot be gained by the Veda,' etc., at the same time teaches that the meditation through which Brahman is attained is of the nature of devotion (bhakti). Next the śloka I, 3, 1 'There are the two drinking their reward' shows that, as the object of devout meditation and the devotee abide together, meditation is easily performed. Then the section beginning 'Know the Self to be him who drives in the chariot,' and ending 'the wise say the path is hard' (I, 3, 3-14), teaches the true mode of meditation, and how the devotee reaches the highest abode of Vishṇu; and then there is a final reference to the object to be reached in I, 3,15, 'That which is without sound, without touch,' etc. It thus appears that there are references and questions regarding those three matters only; and hence the 'Un-evolved' cannot mean the Pradhāna of the Sāṅkhyas.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The commentary proposes different ways of finding those three objects of enquiry in the words of Naciketas. According to the first explanation, 'that which is different fronm dharma' is a means differing from all ordinary means; 'adharma' 'not-dharma' is what is not a means, but the result to be reached: hence 'that which is different from adharma' is a result diferring from all ordinary results. 'What is different from that' is an agent different from 'that'; i.e. an ordinary agent, and so on. (Śru. Prakāś. p. 1226.)

[2]:

The syllable 'Om,' which denotes Brahman, is a means towards meditation (Brahman being meditated upon under this form), and thus indirectly a means towards reaching Brahman.