Satapatha-brahmana

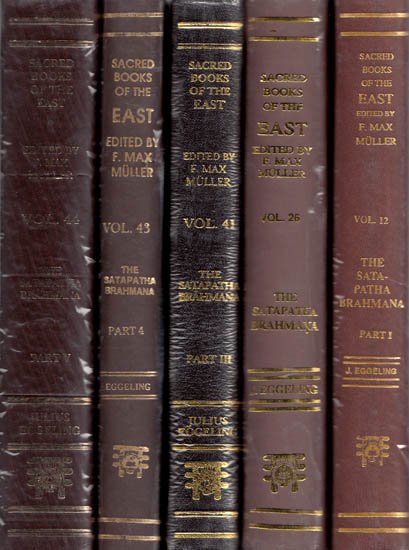

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana I.5.3 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 3rd brahmana of kanda I, adhyaya 5.

Kanda I, adhyaya 5, brahmana 3

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. The fore-offerings (prayāja), assuredly, are the seasons: hence there are five of them, for there are five seasons.

2. The gods and the Asuras, both of them sprang from Prajāpati, were once contending for this sacrifice, (which is) their father Prajāpati, the year: 'Ours it (he) shall be!' 'Ours it (he) shall be!' they said.

3. Then the gods went on praising and toiling. They saw these fore-offerings and worshipped with them. By means of them they gained (pra-ji) the seasons, the year; they deprived their rivals of the seasons, of the year: hence (the fore-offerings are) victories (prajaya), for, assuredly, prajaya is the very same term as prayāja (fore-offering)[1]. And in the same way this one (the sacrificer) wins by means of them the seasons, the year; deprives his rivals of the seasons, of the year. This is the reason why he performs the fore-offerings.

4. The sacrificial food at these offerings consists of clarified butter. Now the butter, indeed, is a thunderbolt, and with that thunderbolt, the butter, the gods gained the seasons, the year, and deprived their rivals of the seasons, of the year. And with that thunderbolt, the butter, he now, in the same way, gains the seasons, the year, and deprives his enemies of the seasons, of the year. For this reason clarified butter forms the sacrificial food at these (offerings).

5. Now this butter is the year's own liquor: hence the gods gained it (the year) by means of its own liquor; and in the same way he also now gains it by means of its own liquor. This is the reason why clarified butter forms the sacrificial food at these (fore-offerings).

6. Let him (the Adhvaryu) not move from that same spot where he may be standing when he calls for the fore-offerings. A battle, it is true, is witnessed whenever any one performs the fore-offerings, and whichever of the two combatants is worsted, that one, no doubt, retreats; and he who obtains the victory, advances still nearer: he (the Adhvaryu) might therefore (feel inclined to) step nearer and nearer (to the fire), and offer the oblations (while moving) nearer and nearer[2].

7. This, however, he should not do; he should not move from that same spot where he may be standing when he calls for the fore-offerings. Let him rather offer the (five) oblations in that part (of the fire) where he thinks there is the fiercest blaze; for only by being offered in blazing (fire), oblations are successful.

8. He (the Adhvaryu), having called (on, and having been responded to by, the Āgnīdhra), says (to the Hotṛ), 'Pronounce the offering-prayer (yājyā) to the Samidhs (kindling-sticks)!' Thereby he kindles the spring; the spring, when kindled, kindles the other seasons; the seasons, when kindled, generate the creatures and ripen the plants. In the same (formula) he also implies the (four) remaining seasons, and in order to avoid sameness, he introduces the others by merely saying each time, 'Pronounce the offering-prayer!' For were he to say, 'Pronounce the offering-prayer to Tanūnapāt!' 'Pronounce the offering-prayer to the Iḍs!' and so on, he would commit (the fault of) repetition: hence he introduces the remaining (seasons or fore-offerings) by merely saying each time, 'Pronounce the offering-prayer[3]!'

9. He (the Hotṛ) now pronounces the offering-prayer (yājyā) to the Samidhs. The samidh (kindler), doubtless, is the spring. The gods, at that time, appropriated the spring, and deprived their rivals of the spring; and now this one (the sacrificer) also appropriates the spring, and deprives his rivals of the spring: this is the reason why he pronounces the offering-prayer to the Samidhs.

10. After that he pronounces the offering-prayer to Tanūnapāt. Tanūnapāt, doubtless, is the summer; for the summer burns the bodies (tanūn tapati) of these creatures. The gods, at that time, appropriated the summer, and deprived their rivals of the summer; and now this one also appropriates the summer, and deprives his rivals of the summer: this is the reason why he pronounces the offering-prayer to Tanūnapāt.

11. He then pronounces the offering-prayer to the Iḍs. The Iḍs (praises), doubtless, are the rains; they are the rains, inasmuch as the vile, crawling (vermin)[4] which shrink during the summer and winter, then (in the rainy season) move about in quest of food, as it were, praising (īḍ) the rains: therefore the Iḍs are the rains. The gods, at that time, appropriated the rains, and deprived their rivals of the rains; and now this one also appropriates the rains, and deprives his rivals of the rains: this is the reason why he pronounces the offering-prayer to the Iḍs.

12. He then pronounces the offering-prayer to the Barhis (covering of sacrificial grass on the altar). The barhis, doubtless, is the autumn; the barhis is the autumn, inasmuch as these plants which shrink during the summer and winter grow by the rains, and in autumn lie spread open after the fashion of barhis: for this reason the barhis is the autumn. The gods, at that time, appropriated the autumn, and deprived their rivals of the autumn;

and now this one also appropriates the autumn, and deprives his rivals of the autumn: this is why he pronounces the prayer to the barhis.

13. He then pronounces the offering-prayer with 'Svāhā! Svāhā[5]!' The Svāhā-call, namely, marks the end of the sacrifice, and the end of the year is the winter, since the winter is on the other (remoter) side of the spring. By the end (of the sacrifice) the gods, at that time, appropriated the end (of the year); by the end they deprived their rivals of the end; and by the end this one also now appropriates the end; by the end he deprives his rivals of the end: this is why he pronounces the offering-prayers with 'Svāhā! Svāhā!'

14. Now the spring, assuredly, comes into life again out of the winter, for out of the one the other is born again: therefore he who knows this, is indeed born again in this world.

15. In order to avoid sameness he prays (alternately) with 'may they accept!' and 'may he (or it) accept[6]!' for he would commit (the fault) of repetition, if he were to pray with 'may they accept!' each time, or with 'may he accept!' each time. By 'may they accept!' doubtless, females (are implied); and by 'may he accept!' a male (is implied): thereby a productive union is effected, and for this reason he prays (alternately) with 'may they accept!' and 'may he (or it) accept!'

16. Now at the fourth fore-offering, to the barhis, he pours (butter) together (into the juhū[7]). The barhis, namely, represents descendants, and the butter seed: hence seed is thereby infused into the descendants, and by that infused seed descendants are generated again and again. For this reason he pours together (butter) at the fourth fore-offering, that to the barhis.

17. Now, a battle, as it were, is going on here when any one performs the fore-offerings; and whichever of the two combatants a friend (an ally) joins, he obtains the victory: hence a friend thereby joins the juhū from out of the upabhṛt, and by him it (or he) obtains the victory. This is why he pours together (butter) at the fourth fore-offering, that to the barhis.

18. The sacrificer, doubtless, (stands) behind the juhū, and he who means evil to him, (stands) behind the upabhṛt: hence he thereby makes the spiteful enemy pay tribute to the sacrificer. The consumer, doubtless, (stands) behind the juhū, and the one to be consumed behind the upabhṛt hence he thereby makes the one that is to be consumed pay tribute to the consumer. This is the reason why he pours (butter) together at the fourth fore-offering, that to the barhis.

19. He pours (the butter) together without (the two spoons) touching (each other). If he were to touch (the one spoon with the other) he would touch the sacrificer with his spiteful enemy, he would touch the consumer with the one to be consumed: for this reason he pours (the butter) together without touching.

20. He holds the juhū over the upabhṛt). Thereby he keeps the sacrificer above his spiteful enemy, he keeps the consumer above the one to be consumed: for this reason he holds the juhū over (the upabhṛt).

21. The gods once said, 'Well then, now that the battle has been won, let us establish the entire sacrifice on a firm basis; and should the Asuras and Rakṣas (again) trouble us, our sacrifice will then be firmly established!'

22. At the last fore-offering they established the entire sacrifice by means of the Svāhā ('hail!'). With 'Svāhā Agni!' they established the butter-portion for Agni; with 'Svāhā Soma!' they established the butter-portion for Soma; and with (the second) 'Svāhā Agni!' they established that indispensable sacrificial cake which there is on both occasions (i.e. at the new- and full-moon sacrifices).

23. And so with the (other) deities respectively[8]. With 'Svāhā the butter-drinking gods!' they established the fore-offerings and the after-offerings (anuyājas), for the fore-offerings and after-offerings, doubtless, represent the butter-drinking gods. With the formula 'May Agni graciously accept of the butter!' they established Agni as Sviṣṭakṛt ('maker of good offering'), for Agni is indeed the maker of good offering. And till this day that sacrifice stands as firm as the gods established it. This is the reason why at the last fore-offering he prays with Svāhā! Svāhā!' according to the number of oblations (there are at the chief sacrifice). After he (the sacrificer) has won his battle, he establishes the entire sacrifice on a firm basis, so that, if after this he should violate the proper order of the sacrifice, he need not heed it; for he will know that his sacrifice is firmly established. Now what with exclaiming 'Vashat,' with offering, and with calling out 'Svāhā,' this same sacrifice was well-nigh exhausted.

24. The gods were anxious as to how they might replenish it, how they might again render it efficient and practise (worshipping) with it, when efficient.

25. Now what was left in the juhū of the butter wherewith they had established the sacrifice, with that they sprinkled the havis (dishes, or kinds, of sacrificial food) one after another, and thereby replenished them and again rendered them efficient, because the butter is indeed efficient. Hence after offering the last fore-offering, he sprinkles the havis one after another, and thereby replenishes them and again renders them efficient, because the butter is indeed efficient[9]. Hence also from whatever sacrificial food he (afterwards at the principal oblations) cuts off (a portion for a deity), that he again sprinkles (with butter), that he replenishes and renders efficient for the (Sviṣṭakṛt) maker of good offering. But when he cuts off the portion for the maker of good offering, then he does not again sprinkle (the sacrificial food out of which the portion has been cut), since after that he will not make any other oblation in the fire from the sacrificial food[10].

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

In reality prayāja (from yaj, 'to sacrifice') has, of course, nothing to do with prajaya (from ji, 'to conquer').

[2]:

Though the author does not state expressly that this change of position in performing the five fore-offerings is advocated by some other ritualists, he apparently argues in this passage against an actually adopted theory and practice, which the Sūtras also mention as optional. In the case of the Adhvaryu changing his position, he is at each successive fore-offering to pour the butter on a part of the fire east of the preceding one. Kāty. III, 2, 18-21.

[3]:

On the necessity of avoiding sameness of ritualistic practices cf. note on I, 3, 2, 8. The five fore-offerings (prayāja, here identified with the five seasons) are addressed respectively to the kindling-sticks (samidh), to Tanūnapāt (or Narāśaṃsa, both mystical forms of Agni), to the Iḍs (personifications of the forms of devotional feeling), to the sacrificial grass-covering of the altar (barhis), and to Agni and Soma (or other deities). Since, in introducing the first fore-offering, the Adhvaryu has mentioned its recipient, he is not to do so in the case of the remaining four.

[4]:

Such as lizards, alligators. Sāyaṇa.

[5]:

See further on, par. 22. As to Svāhā! marking the conclusion of the sacrifice, see the Samiṣṭayajus I, 9, 2, 25-28.

[6]:

The first offering-prayer (to the logs) is 'yê yajāmahe samidhaḥ, samidho agna ājyasya vyantū vāuṣaṭ!' i.e. 'we who pronounce the offering-prayer to the Samidhs,--the Samidhs, O Agni, may accept the butter! vāuṣaṭ!' Similarly at the other fore-offerings; but at the second and fourth, where the object of worship is a single one (viz. Tanūnapāt and the Barhis respectively), 'may he (or it) accept (vetu)!' has to be substituted for 'may they accept (vyantu)!' The difference of number in these verbal forms is symbolically explained as implying a distinction of sex, for the reason that there may be more wives to one man, but only one husband to a woman. The elliptic expression ye yajāmahe is thus explained by Sāyaṇa on Taitt. S. I, 6, 11: 'All we Hotṛ priests that are urged on by the Adhvaryu calling "Recite (thou)!" we do recite, we do pronounce p. 149 the yājyā.' This introductory part of the offering-formula is called āgur, 'acclamation, assent' (Āśv. I, 5, 4); it is alluded to in Mahābhār. Vanap. I2480 (cf. Muir, O. S. T. I, p. 135), and apparently by Pāṇ. VIII, 2, 88 (cf. Haug, Ait. Br. II, p. 133 n.).

[7]:

In making the oblation, the Adhvaryu holds the juhū over the upabhṛt and pours some of the butter from the juhū over the spout of the upabhṛt into the fire. At the third prayāja he empties all the butter remaining in the juhū into the fire, and thereupon, for the fourth oblation, replenishes the empty spoon with half the contents of the upabhṛt, after which he proceeds as before.

[8]:

Cf. p. 118, note 3. The words 'Svāhā Agnim' &c. are preceded by 'ye yajāmahe,' see before, p. 148, note 2.

[9]:

After the Adhvaryu has performed the last fore-offering, he p. 152 steps back behind the altar and sitting down beside the dishes of sacrificial food, anoints, with the butter remaining in the juhū, first the (butter in the) dhruvā, then the several sacrificial dishes; and finally the (butter in the) upabhṛt. Kāty. III, 3, 9.

[10]:

What remains of the dish of sacrificial food, after the oblation to Agni Sviṣṭakṛt (I, 7, 3, 1 seq.) has been made, is eaten by the priests and the sacrificer, and in their case the several portions are basted with butter, as they are cut off, but not the dish of food from which the portions have been taken.