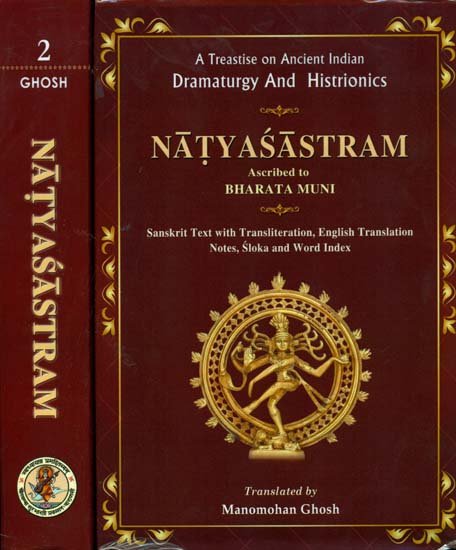

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 3 - Literature on Ancient Indian Music

1. Early Writers (c. 600 B.C .—200 A.C.)

(a) Nārada.

Nārada mentioned repeatedly in later literature on music, seems to be the earliest writer on the subject, and the Śikṣā named after him[1] appears, apart from its interpolated passages, to be a very old work, and it may be as old as 600 B.C., and its teachings may be earlier still. As one couplet[2] from it has been quoted by Patañjali with a slight variation, it is not later than 200 B.C. Like the Pāṇinīya Śikṣa (c. 600 B.C.) it is written chiefly in the Anuṣṭubh metre; and it treats of musical theories in connexion with the singing of Sāmas. The fact that it describes the Gāndhāra Grāma in detail (together with its Mūrchanās) shows clearly that it is much anterior to the NŚ which ignores altogether this Grāma and was written when they become obsolete. The NŚ quotes the NāŚ. (1.3.13) at least once (XXXIII. 227) without naming it. As this śiksā discusses the seven notes in the three Grāmas and the Mūrchanas and Tānas connected with them, the Indian Music seems to have been pretty advanced at the time when this work was composed.

(b) Svāti.

Svāti has been mentioned in the NŚ along with Nārada, but not even a fragment of his teaching has reached us, and we are not sure whether he wrote any work on the subject or anything was written on his views.

(c) Kohala.

In the NŚ (I. 26) Kohala has been mentioned as one of the hundred sons of Bharata and as such he was anterior to the author of this work. From another passage in the NŚ (XXXVI 61) we learn that “śeṣem uttaratantreṇa Kohalaḥ kathayiṣyati” ‘Kohala will speak of the remaining (teachings) on dramaturgy in a supplementary treatise.’ Hence it may be presumed that Kohala was not widely separated in time from the author of the NŚ. Kohala’s opinion has been referred to in Dattila’s work in connexion with Tāla. This is perhaps the earliest reference to his teaching. The Bṛhaddeśi also refers to Kohala’s views no less than five times while discussing notes, Tāna and Jāti. The author of the Saṃgītamakaranda also mentions him twice in the chapter on dance (nṛtya), Pārśvadeva in his Saṃgītasamayasāra names Kohala in the beginning of his chapter on Tāla. In his commentary of the chapters on music, Abhivavagupta while discussing Tāla, refers at least twice to Kohala. From Abhinava’s commentary, it is further learnt that Kohala wrote a work named the Saṃgīta-meru. Hence it is natural that Śārṅgadeva has named him as one of the old masters.

Two other works the Tāla-lakṣaṇa and the Kohala-rahasya, have also been ascribed to Kohala[3]. These may genuinely reflect the the teachings of Kohala. From all these it appears that Kohala was a very important early writer on music.

(d) Śāṇḍilya and Vātsya.

The NŚ has twice mentioned Vātsya and Śāṇḍilya together. Śāṇḍilya not being included amongst the hundred Sons of Bharata, seems to be somewhat later. But one cannot be sure on this point. Śāṇḍilya has not been quoted in an early work. Only the author of the commentary “Tilaka” on the Rāmāyaṇa, mentions him twice in connexion

with the Mūrchanā and the Jāti[4]. And Vātsya is not known to have been quoted by any work.

(e) Viśākhila:

Dattilam is the earliest work to mention Viśākhila.[5] As we have already seen that Dattila was anterior to the NŚ. Viśākhila was also a very old writer on music. The Bṛhaddeśī also once refers to him.[6] The passage in question being somewhat corrupt it has escaped the notice of other writers. It is as follows:

nanu mūrchanā-tānayoḥ ko bhedaḥ? ucyate—mūrchanā-tānayo nunātvantaram (=stu nārthāntaram) iti Viśraṅkhila (=Viśākhilaḥ) etaccāssṃgatam.

(Tr. Now, what is the difference between the Mūrchanā and the Tāna? Viśākhila’s view that the Mūrchanā and the Tāna are identical, is not correct.) Viśākhila has been quoted and referred to at least seven times by Abhinavagupta in his commentary on ch. XXXVIII of the NŚ.[7] Cakrapāṇidatta (c. 11th century) also has quoted from Viśākhila in his commentary on Caraka, Nidāna-sthāna, VII. 7.[8]. The relevant passage is as follows:

Yad uktam Viśākhinā (wrong reading for Viśākhilena)

śamyā dakṣiṇa-hastena vāmahastena tālakah /

ubhābhyāṃ vādanaṃ yat tu sannipātaḥ sa ucyate //

(Tr. As has been said by Viśākhila, the Śamyā is struck by the right hand, the Tāla by the left hand, and that struck by both the hands is the Sannipāta.)

(f) Dattila:

Another very old authority on music was Dattila[9]. Mentioned by the NŚ as one of the sons of Bharata, he is earlier than the writer of this work. But the work going by his name, may not be actually written by him; but its antiquity is great. For the teachings ascribed to him as available in the text named after him, seems to be less developed than that available in the NŚ. For example, according to Dattila, Alaṃkāras are thirteen in number while according the NŚ (XXIX. 23-28) they are thirty-three, and later writers further add to their number. The Bṛhaddeśī makes quotation twice (pp.29-30) from

Dattila. Kṣīrasvāmin (11th century) the commentator of the Amara-kośa (ed. R.G.Oka, Poona, 1913) also quotes passages twice from Dattila.

Abhinavagupta in his commentery on the chapter XXVIII of the NŚ, has quoted passages from Dattila no less than ten times. And another comentator of the Amara-kośa (Vandyaghaṭīya Śarvānanda) also quoted from him the following: Mukhaṃ pratimukhaṃ caiva grabho vimarśa eva ca etc.[10] From this it appears that Dattila wrote not only on music, but also on dramaturgy.

2. The Date of the Nātyaśāstra.

In the Introduction to the volume I of the present work the translator wrote “it may be reasonable to assume the existence of the Nātyaśāstra in the 2nd century. A. C. (p. LXXVI). By the Nātyaśāstra was meant the present text of the work including some spurious passages (p. LXV) Hence the date of the NŚ in its original form will be earlier. After making a closer study of the concluding chapters, the translator is inclined to support the view of the late Haraprasad Sastri who concluded that the work belonged to 200 B.C.[11] But the question will be taken up later on.

3. Early Medieval Writers on Music (200 A.C.—600 A.C.)

(a) Viśvāvasu.

The view of Viśvāvasu on Śruti has been quoted in the Bṛhaddeśi (p.4). But it is difficult to identify him with Viśvāvasu the king of Gandharvas who according to the Mahābhārata was an expert in playing a Vīṇā.

(b) Tumburu.

Tumburu’s view also has been quoted in the Bṛhaddeśī (p.4). But due to the corrupt nature of the passage quoted, this has escaped the notice of the earlier writers. The passage in question is as follows:—

Apare tn vāta-pitta-kapha-sannipāta-bheda-bhinnāṃ catur-vidhāṃ śrutiṃ pratipedire. tathā cāha Tumburuḥ (the last word wrongly read as caturaḥ): uccaistaro dhvanī rukṣo vijñeyo vātajo (wrongly vālajaḥ) budhaih. gambhīro ghanalīnaśca (wrongly nīlaśca) jñeyo’sau pittajo dhvaniḥ. snigdhaś ca sukumāraśca

madhuraḥ kaphajo dhvaniḥ. trayāṇām guṇasaṃyukto vijñeyo sannipātajaḥ.

This quotation from Tumburu occurs in a correct from in Kallinātha’s commentary on the SR (1.3.13-16). Some writers think on the basis of the occurrence of the expression ‘Tumburu-nāṭaka’ in Locana’s Rāga-taraṅgiṇī (12th century) that Tumburu wrote a play. But this tumburu-nāṭaka seems to have meant a kind of dance-drama originating with Tumburu.

(c) The Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa.

Though not a work on music, the Mārkaṇḍeya-purāṇa may be considered in the present connexion; because it gives us valuable informations regarding the musical theory and practice at the time of its compilation. Though here is no direct evidence about its exact age, scholars are agreed about its great antiquity, and according to Pargiter who studied this work very closely, its oldest parts may belong to the third century A.C.[12]. This suit very much the data of music obtained from it. For, it mentions the seven svaras (notes), seven Grāmarāgas, seven Gītakas and as many Mūrchanās, forty-nine Tānas, the three Grāmas, four Padas, three Kālas (wrongly Tālas), three Layas, three Yatis and four Ātodayas. Except the Grāma-rāgas mentioned in this Purāṇa, all other terms occur in the NŚ. The Grāma-rāgas are ignored by the NŚ. They are probably related to the Grāma-geya-gāna (songs to be sung in a village) of the Vedic Sāma-singers as distinguished from the Sāma-singers’ Ārayṇya-gāna or forest songs which were taboo in villages[13]. It seems that the term which may be earlier the NŚ was not recognised by the NŚ, for some reason or other. The three Kālas might also relate to the time required to pronounce short, long and pluta syllables. From these facts, it may be concluded that the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa was not compiled much later than the NŚ. Those who assign a lower date to the Purāṇa refer to the Devī-māhātmya (ch. 81-93) which in their opinion is not much earlier than 600 A.C. This however seems to be far from justified. For Durgā glorified in this Purāṇa was already an important deity in the later Vedic period, the Devī-sūkta being a part of the Khila-

portion of the Ṛgveda. Hence the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa may very well be placed in the 3rd century A.C.

(d) The Vāyupurāṇa.

The Vāyupurāṇa also should be considered in connection with the medieval writings on music. For it contains two chapters (86-87) which treat of the Mūrchanās, Tānas and Gītālaṃkāras[14]. Even if these two chapters are in a very corrupt state, from them one can form a fairly correct idea about the musical teachings of the time. Though this Purāṇa describes the rule of the Gupta dynasty as it was in the 4th century A.C.[15], and though the Guptas, one very great among them being Samudragupta, were patrons of music, these two chapters seem to repeat only what is already available in the NŚ, except that they give the number of Alaṃkāras as thirty. (The second half of the first couplet of the chapter 87 should be emended as follows: triṃśat ye vai alaṃkārās tān me nigadataḥ śṛṇu (see sl.21 below). But the NŚ gives the number of Alaṃkāras as thirty-three (XXIX, 23-28). Another new information available in the Vāyupurāna is the affiliation of Tānas to different Vedic sacrifices. Due to a loss of some ślokas between the two hemistichs of the couplet 41 of the chapter 86, some writers were led to attach these names to Mūrchanās. If these ślokas occuring in the Bṛhaddeśī have not been taken from the Vāyupurāna, they must have been taken from a common source by both these works.

(e) Nandikeśvara.

The Bṛhaddeśī quotes (p.32) in one passage the view of Nandikeśvara on the Mūrchanā. From this we learn that he recognised a class of Mūrchanā consisting of twelve notes. We also know one Nandikeśvara as a writer on abhinaya (gesture) and Tāla. And the two may be identical. The Rudra-ḍamarūdbhava-sūtra-vivaraṇam a commentary on the Māheśvara-sūtras, is also ascribed to Nandikeśvara. This also may be from the hands of Nandikeśvara the author on abhinaya etc. But before the work has been critically studied, one cannot be sure about this. And Nandikeśvara the author of the Abhinaya-darpaṇa as we have seen elsewhere[16] was posterior to the 5th century.

4. Medieval writers of the Transitional Period( 600 A.C .-1000 A.C.)

(a) Śārdūla, Mataṅga, Yāṣṭika, Kaśyapa and Durgaśaskti.

It was during this period that the Rāgas of later Indian music slowly developed from the Grāma-rāgas[17] of early medieval music, which have been mentioned in the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa. The Gīti or the Bhāsā-gīti of various kinds mentioned in the Bṛhaddeśī[18] had probably connection with this Grāmarāga. And from this work, it is also learnt that Śārdūla recognised only one Gīti called Bhāṣāgīti, Mataṅga two Gītis, Bhāṣāgīti and Vibhāṣā-gīti, Yāṣṭika three of them named Bhāṣāgīti, Vibhāṣāgīti and Antar-bhāṣikagīti. Durgaśakti however gave their number as five, viz. Śuddha, Bhinna, Vesara, Gauḍī and Sādhāraṇī. Kaśyapa seems to agree with Yāṣṭika in this regard; but one cannot be sure on this point. The personal view of the author of the Bṛhaddeśī is that the Gīti is of seven kinds: such as Śuddha, Bhinnaka, Gauḍika, Rāgagīti, Bhāṣāgīti and Vibhāṣāgīti. It is probably to demonstrate the fuller nature of his own classification, that he brings in the view of his predecessors, which have been mentioned above. The evidence at our disposal for ascertaining the time of these authorities is meagre. But we are possibly not quite helpless in this matter. For, the term Bhāṣāgīti seems to give some indication as to the upper limit to the age of these teachers. It seems to be evident that bhāṣā in this connection is nothing other than the deśa-bhāṣā or regional dielects or languages, and that is the reason why the songs composed in deśa-bhāṣā were also called Deśī from which the Bṛhaddeśi derives its name. Now bhāṣā came to be accepted as a vehicle of literary expression as early as the 6th century A.C.; for Bāṇabhaṭṭa mentions among his friends one Īśāna who was a bhāṣā-kavi or a poet writing in bhāṣā.[19] Hence it may naturally be assumed that bhāṣā attained some prestige at that time in connection with the music also. In all probability Śārdūla who recognised one kind of Gīti called the Bhāṣāgīti, might have

been an younger contemporary of Bāṇabhaṭṭa. Mataṅga, Yāṣṭika, Kaśyapa and Durgaśakti all of whom might have followed him in later centuries, probably one after another, added to the number of Gītis or Bhāṣāgītis. The new era reached right down to the time of the author of the Bṛhaddeśi who seems to have flourished about the 10th century A.C. when the Bhāṣā-movement may be said to have culminated in the development of New Indo-Aryan languages and bhaṣā became the vehicle of the classical melodies of the Rāga-type.

(b) The Bṛhaddeśī.

The work ascribed to Mataṅga cannot be taken as a work written by Mataṅga. For as we have seen above, Mataṅga’s view has been quoted in the work itself along with the view of other earlier writers. Hence it seems have been compiled by some one other than Mataṅga himself, and was ascribed to the old master evidently for giving it a greater authority. About the date of this work we have given our view above. The fact that Śārṅgadeva recognised Durgaśakti’s view about the number of Gītis in opposition to the one given by the author of the Bṛhaddeśī[20], probably shows that the two authors were not widely separated in time. The Bṛhaddeśī extensively makes quotation form the NŚ.

5. Late Medieval Writings (1000 A.C.-1300 A.C.)

(a) The Saṅgīta-makaranda.

This work[21] ascribed to Nārada, was evidently not from the hands of the author connected with the Śikṣā named after him. The fact that the Rāgas known in later music make their appearance in it, speaks for its lateness. As it has been utilized by Śārṅgadeva (1210-1247 A.C.) it may be tentatively placed in the 11th century A.C.

(b) The Rāga-taraṅgiṇī.

This was composed by Locana-Kavi, the court-musician of the king Vallālasena of Bengal.. It was written 1160 A.C.[22], the year of Vallālasena’s accession

to the throne. He therefore lived one generation earlier than Jayadeva the celebrated author of the Gīta-govinda which was a lyrical poem to be sung with musical accompaniment. From the Rāgataraṅgiṇī it is learnt that the author also wrote other works such as the Rāga-gītasaṃgraha. But these have not come down to us. Locana’s work mentions twelve basic (janaka) Rāgas to which eighty-six derivative (janya) Rāgas owe their origin.

(c) The Saṅgīta-samayasāra.

This work[23] was written by Pārśvadeva of whom we do not know anything more. He was probably a Jain; and as he names Bhoja[24] and Someśvara[25] he was later than these personages. But Śārṅgadeva who mentions them does not mention Pārśvadeva. Pārśvadeva therefore may be placed in the 13th century A.C. and may be considered to be a contemporary of the author of the Saṅgīta-ratnākara. Pārśva’s treatment of Rāgas though pretty exhaustive, is shorter than that of Śārṅgadeva.

(d) The Saṅgīta-ratnākara.

This is the most exhaustive treatise on Indian music. It was written by Śārṅgadeva (1210-1247) a South Indian whose grandfather was a Kashmirian. In the seven chapters of the work, he treats of notes, Rāgas, miscellaneous topics, musical compositions, rhythms, musical instruments and gestures. He describes Śruti, notes, Grāmas including the obsolete Gāndhara Grāma, Mūrchanā, Tāna, Varṇa, Alaṃkāra, Jāti, Vādī, Saṃvādī, Vivādī and Anuvādī notes very clearly, and summarizes whatever has been said by his predecessors. This gives the work a special importance in connection with a critical study of the NŚ. Many things occurring in this latter work when otherwise obscure, become elucidated as soon as they are compared with similar items discussed in the Saṅgīta-ratnākara. As Śārṅgadeva elaborately describes the Rāgas with their late developments, his work serves, as a bridge between the tradition of the NŚ and the works written in late medieval times (after the 13th century) which almost exclusively treat the Rāgas and their different varieties. As these works are not of much importance regarding the study of Indian music in its ancient and early medieval aspects, we refrain from mentioning them.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

NāS (Nāradiya-śíkṣā).

[2]:

“mantro hīnaḥ svarato varṇato vā mithyā prayakto na tamarthamāha |

sa vāgavajro yajamānaṃ hinasti yathendrśatruḥ svaratoparādhāt ||”

Patañjali reads as “dṛṣṭaḥ śabdaḥ svarato varṇato vā” etc. Evidently the author of the Bhāṣya changed the couplet to suit his own purpose.

[3]:

Svāmi Prajñānānanda—Saṃgīta-O-Saṃskṛti (Bengali) vol. II. pp. 347f.

[4]:

Ibid. pp. 352-353.

[5]:

Dattils, śl. 177.

[6]:

See page 26.

[7]:

Pages 14, 15, 24, 34, 41, 72. and 86 of the transcript from Baroda.

[8]:

ed. Haridatta Sastri pp. 473-474.

[9]:

ed. K. Sambasiva Sastri.

[10]:

See the Introduction to this text (Baroda ed.)

[11]:

See JPASB, vol. V. (N.S.) pp. 351 ff.; also vol. VI pp. 307ff.

[12]:

Winterniz. Vol. I. p. 560. The chapter 23 of the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa has been critically edited and published by Alain Daniélou and N. R. Bhatt in ‘Textes des Purāṇa sur la theorie musicale,’ Pondichery, 1959. It reached the present author late.

[13]:

Winternitz, p. 167,

[14]:

Svāmi Prajñānānanda has printed these in his vol. II of the Saṅgīta-O-Saṃskṛti, pp. 484 ff. The Viṣṇudharmottara (C. 8th century) also contains some chapters on music. But these are not of much importance in the present connection. See Textes des Purāṇa sur la theorie musicale ed. by Daniélou and Bhatt.

[15]:

Winternitz op. cit. p. 554.

[16]:

See the Introduction to the Abhinayadarpaṇa ed. M. Ghosh (2nd ed). Calcutta, 1957.

[17]:

See above p. 24.

[18]:

See page 82.

[19]:

Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies Vol. I (1917-20), Grierson, Indo-Aryan Vernaculars, Chapter II, p. 65.

[20]:

See SR II. 1.7.

[21]:

Ed. M. R. Telang.

[22]:

See Kshitimohan Sen, Bāṅglār Saṅgitācārya in the Gītavitāna-vārṣik? Vol. I, 1350 (BE.) Songs of Vidyāpati available in the present text of the Rāgataraṅginī are evidently a later interpolation and hence do not determine its date. See ibid.

[23]:

Ed. Ganapati Sastri. 100. Ibid (II. 5).

[24]:

Ibid (III.5).

[25]:

Ibid (II. 5; IX. 2).